Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s interview with Al Jazeera’s Mehdi Hasan on Head to Head became the subject of much discussion this week. The conversation was filled with tense moments, uncomfortable questions from Hasan and curt responses from the former Sri Lankan leader.

Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s interview with Al Jazeera’s Mehdi Hasan on Head to Head became the subject of much discussion this week. The conversation was filled with tense moments, uncomfortable questions from Hasan and curt responses from the former Sri Lankan leader.

One of the most striking exchanges occurred when Hasan raised the controversial issue of the Batalanda torture camp. This probing question, likely the first of its kind directed at Wickremesinghe by a local or international journalist proved to be an unwelcome reminder of the past, prompting a visibly agitated and perplexed response from him.

“Some people say you should be investigated. During the early part of the civil war the Sri Lankan Government faced an uprising as you know from the JVP, a leftist group whose current leader is the President. There was this Government Commission of Inquiry which found that in the late ‘80’s you were an architect of securing a housing complex which was used for the purposes of illegally detaining, torturing and killing individuals linked to the JVP. The Government Inquiry reported that you quote to say the least knew it was being used for illegal detentions and torture while you were living and working there. You did not know what was going on there? You were not involved?” Hasan asked.

“Where is the report?” Wickremesinghe responded. “Sorry?” Hasan replied, confused. Wickremesinghe pressed again, “Where is the report?”. He confusingly demanded that Hasan read from the report, despite the journalist having just done so.

As the awkward exchange continued, Wickremesinghe threw in another unexpected remark, adding to the confusion and sparking much debate among the public.

“Where is that Commission? Has the report been tabled in Parliament? There must be a Commission report. The Commission report must be tabled. If it is not tabled in Parliament it is not a report,” he repeatedly insisted, casting doubt on its validity.

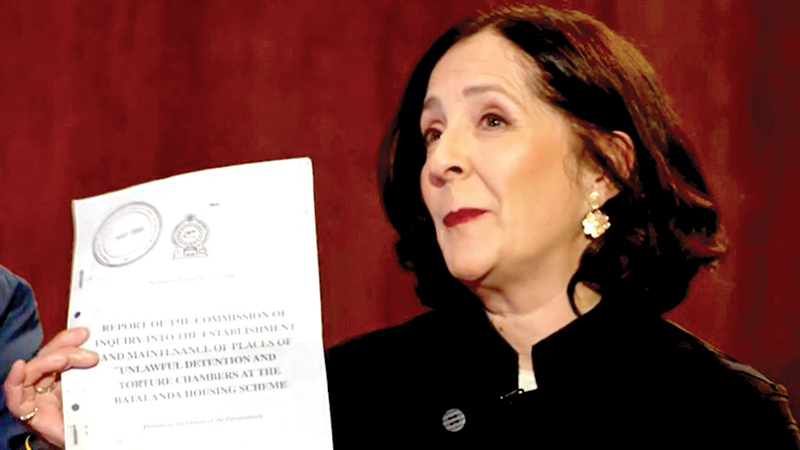

Even though a copy of the report was shown by the panellist, former BBC Correspondent Frances Harrison, Wickremesinghe continued to reject its validity to which Frances responded “It is astonishing”.

Wickremesinghe at a press conference held in Colombo this week attempted to discredit the panel, by suggesting Harrison and another were LTTE sympathisers. “In fact, we had two people who were very much with the LTTE,” he said.

Speaking to the Sunday Observer, Harrison challenged Wickremesinghe to repeat these remarks during his next visit to the United Kingdom.

“I note Ranil Wickremesinghe held a special press conference and tried to suggest I was LTTE for just saying there actually was a Sri Lankan Government commission of inquiry on torture chambers at Batalanda. This is highly defamatory and I invite him to come to the UK and repeat the assertion so that my lawyers can sue him. I will even pay for the airfare – economy class. Sri Lanka wants domestic accountability for the North East but then rejects its own reports on something that happened in the South.” she said.

“I note Ranil Wickremesinghe held a special press conference and tried to suggest I was LTTE for just saying there actually was a Sri Lankan Government commission of inquiry on torture chambers at Batalanda. This is highly defamatory and I invite him to come to the UK and repeat the assertion so that my lawyers can sue him. I will even pay for the airfare – economy class. Sri Lanka wants domestic accountability for the North East but then rejects its own reports on something that happened in the South.” she said.

However the question remains. Does a report compiled by a Commission of Inquiry in fact lose its validity if it is not presented in Parliament as suggested by Wickremesinghe?

According to former Commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) and human rights lawyer, Ambika Satkunanathan the Batalanda Commission was a presidential Commission of inquiry appointed by former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga according to the Commissions of Inquiry Act.

Commissions of Inquiry Act

The Commission of Inquiry Act, first enacted in 1948, grants the President the authority to establish independent Commissions to investigate matters of significant public concern, such as corruption, human rights violations, or political misconduct. Commissions are appointed through a formal Gazette notification and consist of experts or retired judges, depending on the nature of the inquiry. These bodies have the power to summon witnesses, review evidence and make recommendations based on their findings.

While the Act empowers the Commission to investigate thoroughly, it does not grant the authority to issue legal punishment or criminal sentences. The findings and recommendations of a Commission may be presented to Parliament, but it is not mandatory for every report to be formally tabled. These Commissions aim to provide transparency and accountability, though their effectiveness often depends on political support and public trust.

What is the Batalanda Commission Report?

Among the many infamous torture sites, perhaps there is none more known than the Batalanda torture camp or ‘detention centre’. The Batalanda Housing Scheme, part of the State Fertiliser Corporation in the village of Batalanda within the Biyagama Electorate, gained notoriety as an alleged detention and torture site during the 1987–89 JVP insurrection.

Operated by the Counter Subversive Unit of the Sri Lanka Police, the facility was reportedly used to detain, interrogate and torture individuals suspected of having links to the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). This was part of the broader counterinsurgency measures undertaken by the United National Party (UNP) Government, led by President Ranasinghe Premadasa, to quell the armed uprising.

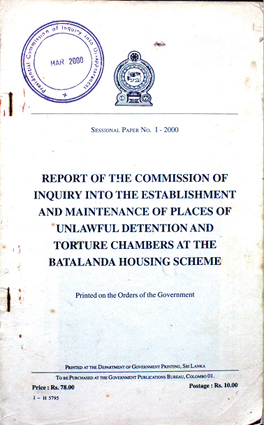

During the 1994 General Election, People’s Alliance Presidential candidate Chandrika Kumaratunga accused Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe of being the key political authority behind the alleged detention centre located in his electorate. Following the People’s Alliance’s victory in both the General and Presidential elections that year, which led to the defeat of the UNP Government, President Kumaratunga initiated multiple Presidential Commissions of Inquiry to investigate human rights violations committed during the 1987–89 JVP insurrection. Among these was the Commission of Inquiry into the establishment and maintenance of unlawful detention and torture chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme. It was tasked with conducting a formal inquiry, summoning witnesses and submitting a report on the alleged detention centre in Batalanda.

“Judge of the Court of Appeal, Justice Dharmasiri Jayawickrema and Colombo High Court Judge Nimal Dissanayaka of Colombo handed over the Batalanda Commission report to the former President Kumaratunga on March 27 1998. Though the appointed time given to the Commissioners was at 5.30 p.m. the President as usual did not divert her routine and met the judges at 8.30 p.m. Having handed over the report, Justice Jayawickrema read extracts from the report and thereafter pondered whether he should hand over to the media a summary of the findings. Secretary to the President, Balapatabendi said that the Presidential Secretary would do so in the near future,” the media reported at the time.

While the report was handed over to President Kumaratunga in 1998 it was only published in March 2000. As Wickremesinghe correctly pointed out in his recent interview, the Kumaratunga Government never tabled it in Parliament.

Political analysts have speculated that this may have been due to the close friendship between the two leaders.

However, during the Al-Jazeera interview, Wickremesinghe argued that the report was withheld because the Government lacked sufficient evidence against him. When Wickremesinghe became Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister in 2001, any possibility of the report being tabled disappeared. Nearly two decades later, it still has not been tabled in Parliament.

Validity of Inquiry Reports

But does this in fact affect its validity? If so, what is the current status of the Committee of Inquiry on 2019 Easter Sunday attacks appointed by Wickremesinghe himself as this report has also not been tabled in Parliament as yet?

According to Ambika Satkunanathan, according to the Commissions of Inquiry Act there is no requirement that the report should be submitted to Parliament. “Hence, its validity is not dependent on whether or not it is submitted to Parliament,” she said. However, she also noted that the absence of such a requirement however, is a shortcoming in the law.

“The reports of many past presidential commissions were not made public. The Batalanda Commission submitted its report to the President at the time Chandrika Kumaratunge in March 1998. It is a valid report. Even if constitutional commissions, such as the Human Rights Commission do not release reports, it does not invalidate them. It merely means the reports aren’t public,” she said.

Calls for action

The People’s Struggles Alliance (PSA) led by the Front Line Socialist Party (FLSP) a breakaway group of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) has now called on the Government to implement the recommendations of the Batalanda Commission.

Addressing a press conference, PSA member Duminda Nagamuwa called on the Government to revoke the civic rights of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe, citing the recommendations of the Batalanda Commission. Addressing the issue, Duminda Nagamuwa challenged the Government to present the long-withheld commission report in Parliament and take legal action against Wickremesinghe for his alleged involvement in the infamous Batalanda torture chamber, where thousands were reportedly tortured and killed during the 1987–89 JVP insurrection.

“We are waiting with great interest to see if the Government will present the Batalanda Commission report and abolish the civic rights of Ranil Wickremesinghe, as recommended by the Commission,” Nagamuwa said. He asserted that this moment presents the JVP with a historic opportunity to legally counter Wickremesinghe’s remarks on the matter.

Referring to the recent Al Jazeera interview where journalist Mehdi Hasan questioned Wickremesinghe about the Batalanda allegations, Nagamuwa said, “This conversation has exposed a very serious and tragic aspect of our country’s politics. The people of this country must watch the full interview to understand the shameless nature of this state and how it plays with people’s lives under the guise of power.”

Nagamuwa condemned Wickremesinghe’s demeanour during the interview, calling his responses “the words of a serial killer who murdered thousands and spread fear across the country.” He criticised Wickremesinghe’s apparent lack of remorse, saying, “With a smiling face, he displayed the vicious mentality of someone who has humiliated the people of this country in front of the international community.”

He also accused past Governments of protecting Wickremesinghe, saying, “The final recommendations of the Batalanda Commission were handed over to the former President. So, why wasthis report never brought to Parliament? Because then-President Chandrika Kumaratunga wanted to protect Ranil’s political future.” Now, with a political shift having taken place, Nagamuwa insisted that the Government must act. This corrupt political regime has lost power. The JVP, which has historically suffered injustice from these serial killers, is now in power. Present the Batalanda Commission report to Parliament,” he said.

Public sentiment at least on social media platforms appears to echo the same demand, with many voicing the need for decisive action. Users have called for the long-suppressed Batalanda Commission report to be handed over to the Attorney General so that appropriate legal measures could be taken.

Others argue that this moment should be seized as an opportunity to finally present the Report in Parliament, making it accessible to the public and ensuring that its recommendations are fully implemented. The growing outcry reflects a broader demand for accountability and justice for the victims of the alleged atrocities.