Reimagining Syria: A Roadmap for Peace and Prosperity Beyond Assad

Executive Summary

For more than a decade, Syria’s crisis has caused unimaginable suffering inside the country and a constant stream of strategically significant negative spillover effects across the Middle East and globally. For much of that time, the conflict has appeared too intense, too complex, and too intertwined in geopolitics to be resolved, with the international community choosing to prioritize managing and containing the symptoms rather than seeking to resolve their root causes. For all intents and purposes, Syria fit the definition of a stubbornly intractable crisis.

However, that all changed in late 2024, when armed opposition groups in Syria’s northwest launched a sudden and unprecedentedly sophisticated and disciplined offensive that captured Aleppo and triggered an implosion of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. In the space of 10 days, Assad’s rule collapsed like a house of cards, dealing Iran’s role in Syria a crippling blow and significantly weakening Russia’s influence too. Since Dec. 9, 2024, an interim government in Damascus has taken shape, dominated by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and a coalition of its Syrian opposition allies.

Despite the controversial history of HTS and the extremely complex set of domestic challenges it now faces, the early policy steps, public messaging, and behavior from Syria’s interim government have been encouraging. A National Dialogue and conference have been held; broad committees have been established to frame a constitutional declaration; and a transitional government and parliament are to be announced in weeks. Outside the country, the international community has moved quickly to engage, recognizing the historic opportunity to reshape Syria, at the heart of the Middle East, for the first time in more than half a century. Dozens of governments and international organizations have traveled to Damascus to establish relations and dialogue with Syria’s new authorities.

Ultimately, engagement offers a far greater chance of influencing and directing the scope and direction of change in Syria than the long-standing policy of isolation that confronted Assad’s regime. Today’s post-Assad Syria remains extraordinarily fragile, with the debilitating effects of more than 13 years of civil conflict ever present. While the prospect of reunifying the country appears to be the most potent point of national consensus in Syria, malign and destabilizing actors remain active, including ISIS, Iran, and perhaps most dangerously, pro-Assad loyalists.

Syria’s transition must be provided the breathing space to succeed. Progress will take time and almost certainly be imperfect. Continued instability and uncertainty is nearly guaranteed. But if the historic opportunity provided by Assad’s departure is to be realized, Syria will require help — principally in the form of sanctions relief. Regional governments stand poised to strategically invest, rebuild, and do the heavy lifting, but they cannot while existing US sanctions remain in place.

For the first time in many years, Syria has a chance to recover and reintegrate into the international system. If the US, Europe, the Middle East, and other stakeholders embrace the right approach, support the right policies, and encourage Syria’s transition to move in the appropriate directions, the world will benefit — and Syrians will find peace. The work of the Syria Strategy Project and the considerable policy recommendations herein present a realistic and holistic vision for realizing that goal.

Introduction and Methodology

This report is the result of intensive joint efforts by the Atlantic Council, the Middle East Institute, and the European Institute of Peace, which have been collaborating since March 2024 on the Syria Strategy Project (SSP). At its core, the project has involved an intensive process of engagement with subject-matter experts and policymakers in the United States, Europe, and across the Middle East to develop a realistic and holistic strategic vision to sustainably resolve Syria’s crisis. This process, held almost entirely behind closed doors, incorporated Syrian experts, Syrian civil society members and organizations, and Syrian stakeholders at every step.

This is the project’s first major publication and one of several products and initiatives aimed at providing policy options that would help resolve Syria’s crisis and inspire action to promote a prosperous, stable, and democratic future for the country. Each organization brings to the project a different scope and unique set of strengths, but all are focused on creating a sounding board for practical and grounded policy conversations on Syria.

To shape and channel the SSP’s efforts, the Atlantic Council, the Middle East Institute, and the European Institute of Peace mobilized a strategic advisory group composed of highly experienced former officials who were consulted throughout the engagement process to ensure policy recommendations remained focused and realistic. This report’s recommendations emerged from six distinct working groups involving more than 100 experts. Over the course of a year, these groups worked intensively on policy issues within their respective areas: accountability and security-sector reform, humanitarian aid, economic recovery, security, governance, and the political process.

Throughout the process, the Atlantic Council, the Middle East Institute, and the European Institute of Peace worked with the Madaniya Civil Society Network to ensure broad Syrian engagement and to identify Syrian scholars to prepare a series of strategic policy briefs relevant to key and timely topics. In total, the SSP conducted 30 working group roundtables, 9 focus group discussions, and over 40 interviews. To ensure wide participation, most of the working group roundtables and interviews took place virtually. A majority of the focus group discussions were held on the ground in locations across Syria, reflecting the breadth of the country’s diversity. Two focus group discussions were conducted virtually due to restrictions caused by the security situation. Engagements with the different stakeholders took place virtually and in person in Washington, Brussels, Doha, Riyadh, Damascus, Latakia, Aleppo, Suwayda, Salamiyah, Paris, and Munich. Participants in the focus group discussions represented different ethnic and religious backgrounds covering all 14 Syrian governorates.

Preventing Syria’s Collapse Through a Representative Political Process

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime on Dec. 8, 2024, marked a turning point in Syria’s modern history. Predictably, the aftermath has been characterized by a complex and fragmented political landscape. Despite the efforts of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the armed group that led the coalition to topple Assad, to command full legitimacy, governance in Syria remains a contentious and evolving process. Various actors — both domestic and international — are maneuvering to shape the country’s transition, making the political process highly dynamic and fraught with challenges.

The collapse of the Assad regime left a power vacuum that was quickly filled by a patchwork of governance structures, most organized by HTS. In some regions, remnants of the former regime’s bureaucracy continue to function under transitional authorities, while in others, newly established local governance bodies seek to assert control. Meanwhile, ad hoc governance structures in northeast Syria continue to function independently from Damascus. The partial collapse of the central government has led to inconsistencies in policy implementation, law enforcement, and basic service provision, further complicating Syria’s path toward stability.

The effectiveness of the transitional process supported by the United Nations has always been hindered by competing interests among domestic and foreign stakeholders, leaving it less relevant to the post-Assad political process. While the core principles of the political transition — credible, inclusive, and non-sectarian governance — remain the foundation of international efforts, implementation has been slow. The primary challenge is the lack of consensus on a new governance model. Factions in northeastern, western, and southern Syria continue to advocate for a decentralized structure, while opposition rebels are pushing for a strong central government to prevent further fragmentation.

Regional and global powers, including the United States, the European Union, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey, will play a significant role in shaping Syria’s political and governance trajectory, but deep divisions persist. The Arab League has re-engaged with Syria, promoting reconciliation efforts and advocating for regional stability, while Western powers continue to condition their support on concrete democratic reforms and clear security guarantees. Since President Donald Trump took office, a gap in vision and action has begun to emerge between the US and Europe. At the same time, Israel’s aggressive efforts — such as carrying out strikes against Syrian military assets across the country as well as making provocative statements supporting division and secession of its ethnic and religious minorities — could further complicate attempts at stabilization by inflaming regional tensions and entrenching hostilities. These actions will antagonize any representative government that will eventually emerge in Damascus, fostering long-term resentment that could push Syria closer to adversarial actors rather than facilitating a sustainable and inclusive regional order. Israel’s actions may also make it impossible for HTS to further moderate and instead empower its more radical elements.

The Syrian people, weary from over a decade of conflict, demand tangible progress in governance and economic recovery. However, rebuilding the state while maintaining security remains a formidable challenge. Local governance structures, despite their limitations, have become crucial in maintaining order and providing basic services. Efforts to integrate these structures into a broader national framework are underway, but political rivalries and territorial disputes slow progress.

A major concern in the post-Assad era is the risk of Syria’s fragmentation and return to civil war. Without a strong central government in place that is capable of exerting itself nationwide, various armed groups remain reluctant to submit to the new authorities and some have sought to assert control over different regions, complicating attempts to unify the country. The presence of extremist elements within this dynamic further threatens the political process, as reintegration and de-radicalization efforts remain contentious topics among stakeholders.

The political process is also closely linked to Syria’s economic recovery. Sanctions relief, reconstruction aid, and foreign investment are essential for rebuilding infrastructure and restoring basic services. However, international donors are hesitant to commit substantial resources without clear assurances that governance structures will remain inclusive, corruption free, and, most importantly, stable. Moreover, donors would like to assert that the new Syria will not become a Salafi jihadist entity, a terrorist safe haven, a revolution-exporting state, a vassal for Turkey, or an overall source of instability for the region. The transitional authorities appear to have so far managed to create a balance in their relations between Turkey and Saudi Arabia, and to respond to concerns from countries like Egypt, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates. The authorities have even prioritized getting rid of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile as a show of goodwill to Western partners. Building on these successes, the interim authorities must work to establish legal and economic frameworks that encourage investment while ensuring that aid does not reinforce the power of armed groups or war profiteers.

Elections also remain a central pillar of the transition, with the interim government having proposed a four- to five-year timeline for implementation — something that triggered concern in the international community. However, in Syria, many fear that premature elections could exacerbate divisions rather than foster unity. The constitutional drafting process that began under UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2254, aiming to establish a legal foundation for future governance, remains irrelevant. Meanwhile, challenges persist around ensuring broad participation and protecting minority rights in the newly established processes. The international community has emphasized the importance of transparency, civic engagement, and legal accountability to prevent a relapse into authoritarianism.

The governance situation in Syria today is in flux, with transitional authorities attempting to navigate a deeply fragmented landscape with extremely minimal resources. While the fall of Assad has opened the door for democratic aspirations, the road ahead is fraught with uncertainty. The success of Syria’s political process will depend on sustained diplomatic engagement, domestic reconciliation efforts, and the ability to create institutions that can govern effectively. Without a comprehensive and coordinated approach, Syria risks prolonged instability and further regional spillover effects. Actions taken in the coming months and years will be crucial to determining whether the country can emerge as a stable and democratic state or remain mired in political and economic turmoil.

Principles

-

The political shift that occurred in Damascus on Dec. 8, 2024, presents an opportunity for a renewed political process, supported by and through the UN, that would establish a national dialogue among Syria’s communities and create a framework for how Syrians can move forward toward a free and democratic country through a representative electoral and constitution drafting processes within a defined timeline. A well-structured framework with trust-building mechanisms can make this process relevant and effective.

-

The ground reality in Syria has evolved since the collapse of the Assad regime, making the traditional regime-opposition framework obsolete. While the architecture of UNSCR 2254 should be revised, its core principles — credible, inclusive, and non-sectarian governance, free and fair elections, and the safe, voluntary return of refugees — must remain intact to align with Syria’s democratic aspirations.

-

The process of bringing together warring parties to a negotiation table to decide what the future of the country will be and how to get there will require strong, united, and coordinated backing from regional and global actors to ensure it retains direction and impact. If international engagement with the process is divided, collective bargaining will prove impossible and Syrians’ democratic aspirations may not be heard.

-

The US, EU, and regional countries that have not engaged yet with the interim authorities should re-establish diplomatic ties in order to prevent state collapse and mitigate regional security threats.

-

The United States and Europe must make clear, inside of Syria and to all external actors, that a unified, stable Syrian state represents the only viable path forward.

-

Premature decentralization may fuel secessionist tendencies and exacerbate pre-existing divisions, tensions, and lines of distrust. Instead, improving local governance can build stability and trust at the community level.

-

Elections are an important pillar of the transition. The transitional period should be time-bound, governed by an interim constitutional framework, and supported by a clear, public roadmap. Strategic sequencing of the transition is essential. Holding elections prematurely, without the right political and legal framework, risks undermining democratic progress.

-

Elections are a process, not an event. They should uphold diversity and pluralism at both local and national levels, taking place only when democratic norms and rule of law are established. A strong and capable Syrian state would help ensure that Syria ceases to be a land bridge for Iranian support to Hezbollah in Lebanon, and may help ease some of Israel’s anxiety toward the new status quo in Syria.

Short- and Medium-Term Recommendations

-

The UN Security Council should adopt a resolution outlining a new framework for the political transition in Syria that would replace UNSCR 2254, while keeping its core principles. The new resolution should create a new integrated mission based in Damascus, allowing a renewed, more targeted, and empowered UN engagement on Syria. The mission’s political work would focus on providing the interim government with technical support for the transition and for governance.

-

The US, Europe, and regional countries should establish a coordination mechanism that will allow them to develop a common approach and to engage directly with the Syrian interim authorities to promote measures that will contribute to regional and international stability while fulfilling Syrians’ aspirations.

-

The US should re-establish diplomatic relations with Syria and utilize its leverage, like sanctions and foreign aid, to incentivize the interim authorities to create representative governance capable of improving living conditions nationwide and preventing any further fragmentation of the country.

-

Building on the National Dialogue Conference held on Feb. 25, the interim authorities should organize more inter-community dialogue sessions that allow engagement between Syrians from different areas at the local level, fostering reconciliation and practical problem-solving.

-

Acknowledging the fragile balances both within the interim government itself and across Syria’s diverse social fabric, the interim government should commit to gradual democratic reforms that ensure broader political participation. Additionally, it should announce a clear transitional period timeline that leads to free and fair elections, the drafting of a constitutional declaration, and a permanent constitution that represents the aspirations of the Syrian people. Such bottom-up participation can only be guaranteed through sustained support for civil society groups, placing an emphasis on civic rights, electoral awareness, capacity building, strengthening local governance, and adopting lessons learned from successful transitions elsewhere.

-

International donors should invest in governance-oriented education, training, and capacity-building programs.

-

Syria’s interim government should preserve existing state structures where possible and utilize existing governing expertise, especially among defectors from the military and the police who were not involved in any bloodshed.

-

Syrian authorities should make a public pledge to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of everyone, ensuring they are free from discrimination. This includes safeguarding the rights to freedom of movement, assembly, and expression.

-

The US should carefully calibrate foreign security assistance — including weapons sales, training, defense infrastructure support, and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs — to influence Syria into countering Iranian influence, cooperating on counterterrorism, and ending Russia’s military presence. Given Syria’s reliance on Soviet weapon systems, leveraging these tools requires coordination with regional partners (Turkey, Jordan, Israel) and ensuring that incentives outweigh Syria’s potential needs from Russia and Iran.

Long-Term Recommendations

-

Syria’s interim government should promote local governance structures that embrace power-sharing and representation in different regions, ensuring autonomy on local governance decisions.

-

Syria’s interim government should support an inclusive constitutional drafting process that guarantees equal rights for all Syrians, including ethnic and religious groups.

-

International donors should condition financial assistance on the establishment of democratic institutions and economic reforms, and they should ensure that reconstruction funds are not monopolized by armed factions or war profiteers.

-

Syria’s interim government should establish legal frameworks to resolve disputes and provide a form of compensation for land and property confiscated, occupied, or destroyed during the war.

-

Regional governments should encourage HTS to publicly renounce extremist ideology and integrate into a legitimate political process, and develop initiatives to reintegrate former extremist fighters and prevent radicalization among youth.

-

The United States should work with neighboring states to prevent foreign influence from destabilizing post-war Syria.

-

Syria’s interim government should determine a representative and realistic national mode of governance to work toward, through the lens of a long-term political settlement for the country.

-

Syria’s interim government should break the long-running cycle of inefficiency, corruption, and security-heavy governance by moving toward increasing levels of local authority over decision making.

Addressing Syria’s Security Challenges and Avoiding Creating More

After nearly 14 years of civil conflict, the security dynamics in Syria are extraordinarily complex, with multiple ongoing and potential lines of hostility, involving a wide range of internal and external state and non-state actors. The degradation of traditional state security structures and proliferation of local, ethnic, sectarian, and tribal military factions always made the prospect of peace and stability an overwhelming consideration. However, with the fall of the Assad regime, a central driver of division and conflict has been removed from the equation and a narrow window is now open, offering an opportunity for de-escalation, demilitarization, reconciliation, reunification, and, ultimately, recovery.

While an active DDR process is underway, it faces considerable challenges in dealing with non-Syrian fighters as well as armed factions in the south and northeast. Despite progress in dissolving Syria’s former armed forces through a process of registration and settling of status, there are clear signs that a regime loyalist insurgency may be developing.1 Having spent 2024 sustaining its own resurgence,2 the Islamic State (ISIS) looks poised to attempt to exploit security vacuums and socio-political uncertainty to sow more chaos and to resurge further.

Geopolitically, Syria has long represented an open wound in the heart of the Middle East, exporting instability and driving division in the region and beyond. While much of the international community has acknowledged the historic opportunity that an effective and successful transition in Syria could represent, there are causes for concern. Iran’s losses resulting from Assad’s departure are historic and potentially game-changing, but any breakdown into civil conflict will open the door for a malign Iranian return. Israel has repeatedly declared its security concerns vis-à-vis the interim government in Damascus and acted upon them — carrying out more than 600 airstrikes in December 2024,3 occupying new territory in the Golan Heights,4 conducting near-daily ground incursions, and demanding the complete demilitarization of southern Syria.5 Turkey already has military proposals on the table with Damascus that would put it in a position to challenge or deter Israel’s current freedom of maneuver in Syria.6

Meanwhile, Turkey’s long-standing hostility toward the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in northeastern Syria may be resolved via a fresh peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK);7 but if the SDF cannot be integrated into the new Syria, some form of conflict will be all but guaranteed.8 The United States has a pivotal role to play in this regard, having encouraged and actively facilitated talks between the SDF and Syria’s interim government since December 2024. The conclusion of an SDF-Damascus agreement on March 10, stipulating that the SDF would dissolve and integrate into the Syrian state, was an extremely encouraging development. Its implementation will prove key to determining stability.

The US government, as well as international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), could also play an extremely valuable role in assisting, guiding, or advising the ongoing DDR process in Syria — embracing lessons learned from other cases abroad and the relevant expertise of practitioners and experts.

But ultimately, the stance Trump’s administration takes on Syria will come to define a lot — on the future of northeastern Syria but also of the country’s wider chances of recovery. Without meaningful US sanctions relief, the Syrian economy will remain in pieces and the resulting humanitarian suffering could, eventually, trigger renewed instability and conflict. Only malign actors stand to benefit from such an eventuality.

Principles

-

Above all else, the international community must prioritize the stability of Syria.

-

A unified Syria whose governmental institutions are representative of all of the country’s diversity and geography will present the best chance of long-term stability.

-

The fall of Assad’s regime provides a historic opportunity to foster a friendly and cooperative Syrian government that is integrated into the region and projects stability.

-

Neither the Iranian government, its military apparatus, nor their various proxies should be given the opportunity to return to Syria.

-

Russia should not be permitted to re-establish strategic military capabilities on Syrian soil, including at its air and naval bases in Latakia and Tartous.

-

Transnational terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS will seek to expand by exploiting uncertainty or instability in Syria. While Syria’s interim government must dedicate sufficient resources to countering this threat, the international community will need to play a significant role for an interim period.

-

US troops do not need to remain in Syria forever, but their support for an interim period remains vital, to ensure security vacuums are filled, ISIS and al-Qaeda movements are monitored and neutralized, ISIS-linked detainees in prisons and camps in northeastern Syria remain secure, and the SDF achieves and implements a just and durable deal with Damascus.

-

Terrorist designations on HTS and associated individuals offer the international community significant leverage, which should be utilized to influence political and security decision-making in Damascus. Clear conditions with benchmarks and timeframes should be conveyed to the interim government to utilize this leverage to incentivize good behavior, better and broader governance, and transitional progress in Syria.

Short- and Medium-Term Recommendations

-

Following the signing of the March 10 integration agreement, Syria’s interim government and the SDF must work to implement the terms of the deal and reintegrate northeastern Syria into the country. While both sides will need to display flexibility, the SDF’s leverage is declining (amid Syria-wide calls for unity and integration as well as well-founded expectations that the Trump administration will withdraw from Syria) and a peaceful implementation of the deal must be guaranteed.

-

The US and its allies and partners must utilize their influence to ensure the implementation of the Damascus-SDF agreement, pressing for a just and durable deal that reunifies Syria, while protecting the rights of Kurds and other communities.

-

To build upon both the March 10 agreement between the SDF and Damascus and the PKK’s recent announcement of a cease-fire and potential dissolution, the US must ensure that the SDF abides by its offer to expeditiously remove from Syria all non-Syrian PKK cadres operating within the SDF.

-

The US, along with allies and partners, should cautiously and conditionally engage Syria’s interim government around their shared interest in countering ISIS and al-Qaeda. Some of this engagement and collaboration has already begun, but it should incorporate more governments and be better coordinated, initially around deconfliction and intelligence sharing.

-

The US must engage directly at high levels with Turkey to resume and invest in bilateral deconfliction and de-escalation mechanisms in Syria, with a focus on the northeast. This should aim initially to reinforce the cease-fire in eastern Aleppo but then broaden to consider a mutually acceptable roadmap for the security dynamics of Syria. This roadmap would factor in a timetable for a US military withdrawal from northeastern Syria — conditioned upon facts on the ground, such as the implementation of the SDF-Damascus deal, the handover and securing of the ISIS prisons and camps, and the integration of SDF forces into Syrian state commands.

-

In addition to investing in bilateral contact and coordination with Turkey, the US military and Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) should proactively support and work with an emerging regional security coordination framework involving Iraq, Jordan, and Turkey. This fledgling regional coalition will help to support an eventual US disengagement and transition to regionally backed local authority.

-

While acknowledging Israel’s security concerns, the international community’s posture toward Syria must prioritize de-escalation. Any further Israeli expansion into Syrian territory must not be allowed; Israeli military strikes on the interim government must stop; territorial control must revert to the lines agreed in 1974; and Israeli attempts to interfere with, provoke tensions within, and otherwise exploit minorities to destabilize Syria must cease. If these lines are not drawn and expectations placed publicly on the table, continued inflammatory Israeli actions risk triggering serious internal divisions and conflict inside Syria, and they could provoke an escalatory spiral involving potential threats toward Israel.

-

While US funding of the prisons and camps in northeastern Syria will need to continue for now, America’s European and Arab partners must step up their commitments — both through financing of security and humanitarian assistance to the facilities as well as covering the costs of repatriating men, women, and children from Syria.

-

The United States, United Kingdom, and European Union should convey clear and realistic conditions to HTS and associated entities for their potential removal from designation and sanctions lists. These conditions should include implementing justice and accountability measures against those guilty of crimes, the formation of a more representative government, the expulsion of non-Syrian jihadist operatives from positions of authority, and demonstrated efforts and success in countering transnational terrorism on Syrian soil.

-

Preliminary dialogue and cooperation between Syria and its neighbors over border security should intensify, to ensure malign state and non-state actors are not afforded the opportunity to smuggle people, weapons, drugs, or other assets into or out of Syria.

-

The interim government must be dissuaded from providing Syrian citizenship to foreign fighters; and foreign nationals subject to external arrest warrants and terrorist designations must not hold formal government positions.

Long-Term Recommendations

-

The international community should consider forming a coalition or other multilateral mechanism that would meet regularly to coordinate a shared approach to security challenges and threats emanating from Syria. This would help reduce the chance of rivalries, misunderstandings, and tensions.

-

Syria’s interim government must provide, and abide by, guarantees to the international community that Syria will not become a safe haven for transnational terrorism.

-

The international coalition against ISIS should develop and commit to a long-term strategy aimed at preventing the terror group from resurging, including in Syria.

-

Should Syria’s transition succeed, the US should seek to negotiate long-term and conditions-based access to Syrian airspace for counterterrorism purposes.

-

Should Syria’s transition fail and serious civil conflict resume, the US should use its presence on the ground, contacts with internal actors, and influence on the international stage to press for de-escalation. Any Iranian or Russian role in resumed conflict should be called out, sanctioned, and challenged diplomatically.

Building a Stable Economy That Would Bring Syrians Back

Prior to Assad’s departure, Syria’s economy was in dire straits and humanitarian conditions were spiraling. At the end of 2024, at least 90% of Syrians were living under the poverty line,9 the Syrian pound (SYP) had lost 99% of the value it held in 2011,10 at least 70% of the population relied on aid,11 and the cost of living continued to rise. More than half of Syrians remained displaced, either internally or as refugees abroad.12 Meanwhile, fatigued by Syria’s seemingly intractable problems and strained by acute crises in Sudan, Gaza, Ukraine, and beyond, the international community’s commitment to funding the humanitarian response in Syria was waning, with the UN aid fund having received just 28% of its estimated requirements in late 2024.13

Though the collapse of the Assad regime brought with it a nationwide sense of euphoria and a renewed drive for Syrian unity, Syria’s economy has not recovered and the humanitarian crisis persists. To make matters even more challenging, the liquidity crisis has worsened, with the SYP value often fluctuating wildly, adding further to the strains placed on living conditions. While the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) — the governance arm of the SDF — had previously sold its oil supplies to Damascus under Assad’s rule, that trade stopped in December 2024, even as Iran’s large-scale provision of oil to Syria also ended. That effectively cut Syria’s oil supply altogether — though small-scale AANES trade resumed in mid-February 2025.14

Buoyed by the historic and strategic opportunity presented by Assad’s departure to reshape the Middle East, regional states engaged quickly and substantively with the interim government in Damascus. To boost Syria’s economy and ameliorate worsening humanitarian conditions, Turkey has proposed providing electricity directly into the grid via floating power stations,15 Qatar has suggested paying public-sector salaries,16 and Saudi Arabia has proposed large-scale oil deliveries.17 Wealthy Syrian businessmen and major regional investors are also primed with reams of proposals to begin work on significant reconstruction and critical infrastructure rehabilitation.

While such initiatives would have a dramatic and almost immediate effect in Syria, they remain impossible while US sanctions are in place.18 In early January, President Joe Biden’s outgoing administration introduced six-month sectoral waivers through General License 24.19 Though a symbolically significant signal, in practice those temporary measures have done nothing to alter the bank de-risking problem, with Syrian financial institutions still refusing to process transactions. The EU lifted sanctions on Syria’s energy and transport sectors, four banks, Syrian Arab Airlines, and activities linked to reconstruction on Feb. 24, 2025.20 Yet American sanctions remain determinant. Without changes to the US sanctions regime, little is likely to change in Syria.

While the existing make-up of Syria’s interim government presents obvious challenges and policy dilemmas, the stability of Syria should be at the forefront of international calculations. Sanctions remain vitally important elements of international leverage and should be used to incentivize more and better behavior, as well as a widening of political representation. But the clock is also ticking, and withholding sanctions relief for months risks guaranteeing the eventual collapse of the transition.

On the humanitarian aid front, donor funding remains dangerously low while the need to achieve record levels of assistance has never been greater. The international community will gather in Brussels again in May 2025 to coordinate support for Syria.

Principles

-

A post-Assad Syria will have the best chance of recovery and international integration if it embraces a free market economy model.

-

Refugee repatriation needs to be coordinated with the provision of humanitarian assistance to ensure that as Syrians return home, they do not add to the economic, social, and security problems.

-

Assad’s departure, Iran’s strategic defeat, and a significant reduction in Russia’s influence in Syria all represent a historic opportunity to foster and support a Syria that is stable and plays a productive and constructive role in the international community.

-

After more than a decade of division, Syria’s reunification will be facilitated greatly by increased levels of interconnectivity, particularly through trade and other commercial exchange — especially across long-standing conflict lines, into and out of the northeast, northwest, south, and the coast.

Short- and Medium-Term Recommendations

-

The US should urgently consider a conditional lifting of sanctions (with integrated snap-back mechanisms) for core sectors of Syria’s economy to help facilitate targeted and strategic investment in energy and other critical infrastructure, as well as civilian government institutions, reconstruction, and other humanitarian and early recovery sectors. At a minimum, General License 24 and supplementary waivers should be permanently extended to more effectively assuage bank de-risking concerns. Like the EU, the US should revisit the designation of Syria’s Central Bank as a sanctioned entity, due to its key role in managing the transitional economy. Such steps will be vital in ensuring that a fragile transition avoids collapse, while broadening in representation and commitment to rights.

-

The US and Europe must establish a working dialogue focused on better coordinating their sanctions measures, whether that entails issuing waivers, lifting sanctions, or maintaining restrictions. This will add more policy clarity and collective leverage diplomatically, while also assisting financial institutions and potential donors and investors to better understand the legal environment in which they can and cannot operate.

-

The interim government should take swift and clear steps to reunify and standardize economic systems and policies that have taken root in different regions of Syria over the past 14 years. This should include re-establishing the SYP as the national currency, standardizing internal and cross-border customs duties, simplifying and stabilizing exchange rate practices, and prioritizing fair competition as businesses previously restricted by geography now look to expand.

-

A multilateral entity should be established for the US, Europe, regional states, the UN, and other stakeholders to convene regularly to discuss and coordinate potential early recovery, investment, and other strategic humanitarian assistance steps toward Syria.

-

While some level of sanctions remains on Syria, sanctioning governments should work to establish a resource hub for NGOs to access legal advice and legislative expertise to help ascertain best practices and avoid diverting otherwise valuable resources.

-

Regional proposals for energy provision and civil-service salary payments should be provided the space to begin work. But to get there, direct and high-level diplomatic and working-level discussions will be needed first — especially with the US government.

-

Amid continued US sanctions and other restrictive measures, there is an acute need for transparent and accessible financial mechanisms to ease the flow of money into and across Syria. The US and allies should establish a formal and widely accepted financial channel and transaction mechanism in order to enable the interim government to prioritize and fund the urgent reconstruction and rehabilitation of Syria’s electricity, energy, residential, and transportation infrastructure. International governments and companies are poised to step back into the Syrian market, particularly in electricity, oil and natural gas, and construction. A proactive working group or communication mechanism should be established with sanctioning entities, as well as with financial institutions, to shape and implement such mechanisms.

-

While Syria’s fragile transition continues, humanitarian efforts should be coordinated with the interim government in Damascus but directed through a localized approach, taking advantage of Syrian local actors’ contextual awareness and untapped capacity. Free and unfettered access to aid must be guaranteed.

-

Humanitarian and early recovery needs should be defined before remedies are discussed. This will require NGOs to be part of an aid policy conversation involving the diverse breadth of Syrian society.

-

The return of internally displaced Syrians and refugees to their places of origin is a natural consequence of Assad’s departure. Regional states hosting large numbers of refugees have already begun introducing incentives to encourage returns. As these numbers grow, additional humanitarian assistance will inevitably be required, and the specific needs of female returnees of all ages will need to be addressed.

-

Countries hosting Syrian refugees should adopt mechanisms to allow them to temporarily return to Syria to assess conditions and return to their refugee status in the host country if necessary.

-

Syria’s neighbors should reduce or remove tariffs on cross-border trade to encourage and facilitate a revitalization of Syrian business and economic activity.

Long-Term Recommendations

-

The interim government must implement a free market economic policy model that ends long-standing Syrian protectionism and corruption and supports a thriving private sector, welcomes foreign direct investment, and stimulates entrepreneurship and small- and medium-sized enterprise. The interim government — with support from international institutions — should also move to develop a public-private partnership framework to facilitate private-sector investment (local and foreign). At the same time, it needs to preserve state assets and ensure sufficient monitoring power over the quality-pricing balance in specific key sectors, including education, healthcare, and fuel.

-

The interim government should also reach beyond tactical diplomacy and engage with the international community — governments and businesses alike — to develop foreign trade deals, transnational business networks, and strategic economic diplomacy.

-

Syria’s interim government must avoid replicating a long-standing investment imbalance favoring so-called “useful Syria” over geographically “peripheral” regions in the northwest, northeast, east, and south.

-

The international community should consider prioritizing a readjustment of NGO and donor-implementing funding cycles to replace the long-standing model of repeated emergency response with longer-term planning.

-

The international community should explore potential financial technology solutions for conducting swifter financial transfers into and out of Syria.

-

The international community should regularly and systematically engage Syria’s diaspora to assess refugee return sentiments, returnee humanitarian needs with a focus on the specific needs of women and girls, and the effects of continued sanctions as well as temporary waiver measures.

Advancing Justice and Accountability

The fall of the Assad regime marked a pivotal moment in Syria’s history, offering a unique opportunity to address the injustices of the past and pave the way for a more just and accountable future. In the aftermath, several critical priorities have emerged to guide the nation’s transition toward justice and reconciliation.

One of the foremost concerns is the fate of forcibly disappeared individuals and the reunification of detainees with their families. Throughout the civil war, the Assad regime detained countless individuals, leading to the enforced disappearance of more than 100,000 people, as has been documented by Syrian and international human rights organizations. The transitional authorities, with the support of the UN Independent Institution on Missing Persons in Syria (IIMP), face the formidable task of tracing the missing persons and expediting the release of unjustly imprisoned individuals. This effort is crucial to provide closure for families and help heal the deep emotional wounds inflicted by years of separation and fear. This process involves exhuming mass graves, analyzing forensic evidence, and ensuring that those responsible are held accountable. However, efforts to start recovery and identification processes from mass graves are yet to be established, leaving tens of thousands of families in limbo as they wait to confirm the fate of their loved ones.

Documenting the atrocities committed during the war, by the Assad regime and all armed groups, is essential for establishing an accurate historical record and supporting future prosecutions and national reconciliation. Numerous organizations, both local and international, have collected evidence ranging from survivor testimonies to physical evidence from crime scenes. The Syrian authorities, in collaboration with these organizations, must consolidate and preserve this information to prevent the loss of crucial evidence and to inform truth-telling processes. This documentation serves as a foundation for justice and reconciliation efforts.

Establishing inclusive and meaningful justice processes is vital for ensuring that all victims receive recognition and redress. In recent years, court cases and investigations have been initiated in Europe under the principle of universal jurisdiction. European courts have provided a pathway for accountability when it was impossible to achieve in Syria and have handed down landmark decisions. Still, these cases cannot be a substitute for a Syrian-owned and Syrian-led justice process. This may involve setting up special tribunals or courts to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity as well as utilizing international expertise and mechanisms where possible. The interim authorities have welcomed the International Criminal Court (ICC) chief prosecutor in Damascus and met with him in Brussels. However, as the ICC has no jurisdiction over Syria, which is not a member state of the Rome Statute that established the ICC, the court cannot prosecute international crimes committed in Syria. Alternative mechanisms, such as hybrid courts combining international and domestic legal principles, are likely to be necessary in order to prosecute war criminals. The Syrian authorities have expressed a commitment to pursuing accountability, with leaders like Ahmed al-Sharaa vowing to “hunt down and punish” officials implicated in atrocities. However, challenges persist, especially with the interim authorities’ lack of capacity across all sectors. The additional dilemma of where to draw the line between a need for justice on the one hand and forgiveness on the other is a particularly sensitive issue — but one that needs clarity. Moreover, securing evidence and ensuring fair trials remain significant hurdles. Lastly, it is essential that perpetrators from all sides are held accountable, not only the members of the former regime, for the justice process to be credible.

Achieving justice and accountability in post-Assad Syria requires robust international support. The UN and other international bodies have expressed a readiness to assist in evidence-gathering and the establishment of accountability mechanisms. Despite earlier reluctance, the interim authorities have been more open to allowing UN accountability bodies to establish a presence in Damascus. However, the interim authorities have not outlined clear plans or started any process leading to justice and accountability for Syrians. The country’s fragile economic and security conditions, coupled with the severely limited capacity of the interim authorities, seem to have hindered the ability to plan or implement any transitional justice processes. Collaborative efforts with civil society organizations, international partners, and the Syrian diaspora are essential to ensuring that all victims are represented and that the pursuit of justice is comprehensive and inclusive.

However, the path to justice in Syria is fraught with challenges. The escape of many high-ranking officials complicates accountability efforts, as does the lack of a legal framework for war crimes trials within the country. Establishing a credible administration and an independent judiciary committed to the rule of law is crucial for the legitimacy of the new justice system. Moreover, ensuring that the new government does not replicate the oppressive tactics of the past requires vigilance and continuous reform.

Lastly, transitional justice should go beyond criminal prosecution. It is necessary to design, in consultation with Syrians, a comprehensive process that includes a truth-telling and reconciliation component in order to guarantee a durable peace. Such a process can build on the experience of South Africa, for instance. Transitional justice should also include a reparation and compensation component, addressing the widespread violations of property rights.

The international community’s role in supporting these efforts, both morally and materially, cannot be overstated. The fall of Assad’s regime opens a new chapter for Syria, one that holds the promise of justice, accountability, and reconciliation. By focusing on the reunification of families, uncovering the fate of the missing, documenting atrocities, and establishing inclusive justice processes, Syria can begin to heal the wounds of the past.

Principles

-

A successful general amnesty in Syria should be transparent, legally sound, and balanced between reconciliation and justice. It must clearly define its scope, ensuring that war crimes and crimes against humanity are excluded while providing fair legal oversight. Reintegration programs, victim support, and transitional justice mechanisms are essential for long-term stability. Security risks should be managed carefully, and the process must gain domestic and international legitimacy by involving civil society and UN bodies.

-

Syria can learn from Iraq’s flawed de-Baathification by avoiding broad purges that dismantle state institutions and fuel sectarian divisions. Iraq’s approach led to governance collapse, insurgency, and economic turmoil, highlighting the need for Syria to pursue a phased, transparent, and inclusive transition. Instead of mass exclusions, Syria should prioritize targeted accountability, reintegration of low- and mid-level officials, and economic stability to prevent further unrest.

-

A reform of Syria’s judicial system must guarantee impartiality and the independence of justice from executive power as well as establish an avenue to hold military, security, and judicial personnel accountable.

-

Reparation systems should be hybrid with both collective and individual components. They should be oriented toward victims and survivors and take into account the gendered impact of destruction.

-

There should be a holistic approach to security sector reform as it requires legal, institutional, and cultural changes, including the prioritization of securing and protecting citizens rather than the state.

-

A successful process of national reconciliation in Syria must be carefully designed to align with the country’s unique cultural, social, and historical context. While reconciliation models from other nations — such as South Africa, Rwanda, or Bosnia — can offer valuable lessons, they cannot be applied wholesale due to Syria’s distinct religious, ethnic, and political dynamics. Any reconciliation effort must take into account Syria’s deeply rooted traditions of conflict resolution, tribal and communal relationships, and the role of religious institutions in fostering dialogue. Ultimately, it is the Syrian people, with their firsthand experience of the conflict and its consequences, who must lead the development of a reconciliation framework that ensures justice, inclusivity, and long-term stability. External actors can provide support, but the process must remain domestically driven to foster genuine national unity and healing.

Short- and Medium-Term Recommendations

-

Syria’s interim government should formally join the Rome Statute of the ICC and authorize its jurisdiction retroactively to 1963 through an official declaration. Furthermore, the authorities must revise national laws to ensure full compliance with the principles of the Rome Statute and international legal standards; and Syria should become a signatory to the seven major international human rights treaties, including the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons From Enforced Disappearances.

-

Syria’s interim government should safeguard civilians from harm and uphold their right to security. When needed, the authorities should deploy security forces to shield religious and ethnic minority communities who may be viewed as affiliated with the Assad regime.

-

The Syrian interim authorities, with the support of the UN, and in collaboration with civil society organizations, should prioritize protecting evidence and sensitive sites such as mass graves and detention centers.

-

Syrian authorities should ensure that detentions abide by the rule of law and meet international standards. Authorities should be transparent about individuals detained, and none should be held incommunicado.

-

Syrian authorities should ensure the independence of justice in order to restore the public’s trust in the ability of the judiciary to be fair and neutral. By improving case management, allowing public access to trials and court records, increasing salaries for judges to mitigate corruption, and establishing protection for judges and lawyers from executive overreach, Syrians can once again place their trust in the system.

-

The Syrian interim authorities should fully collaborate with civil society organizations that have documented violations and international crimes for over a decade and draw on their expertise. They should use their guidance in designing transitional justice and reconciliation processes.

-

Syrian authorities should prioritize mapping victims’ claims and types of property destruction and loss, learning from past and current experience (including in other contexts) and taking into account the gendered impact of destruction as a first step toward reparation and compensation.

-

Syrian authorities should establish an independent and impartial mechanism that not only brings together Syrian civil society organizations but is also carefully designed to align with the social, cultural, and political realities of Syria. By incorporating diverse voices from Syrian society — victims, legal experts, grassroots activists, and community leaders — it can effectively document past and ongoing accountability efforts, identify critical gaps in justice and redress, and chart a clear path forward. Such an approach is essential to fostering a sense of local ownership over the accountability process, preventing external interference from overshadowing Syrian-led initiatives, and ensuring that any steps taken are both practical and culturally resonant.

Long-Term Recommendations

-

The Syrian interim authorities, in collaboration with the UN and Syrian civil society, should establish a prosecution mechanism to judge perpetrators of international crimes, in line with international standards.

-

The Syrian interim authorities, in collaboration with Syrian civil society and with the technical support of the UN, especially victims’ associations, should develop a nation-wide truth-telling and reconciliation process that allows all Syrians to have their voices heard and that grants amnesty to former members of the regime who have not committed serious crimes.

-

Syrian authorities should abolish or amend legislation that grants immunity to security and army personnel.

-

The interim authorities should develop a plan and establish a mechanism for house, land, and property restitution and compensation that guarantees the rights of women and girls to protection from discrimination and to equality in both law and practice. This plan should be formulated in line with the UN Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons (the “Pinheiro Principles”). Alternative judicial processes should be proposed to address property claims.

-

Syrian authorities should prioritize establishing a database for records related to war crimes and human rights violations committed by the Assad regime and allow citizens access to such data, while ensuring transparency.

Annex I: Surveying Syria’s Post-Assad Security Threats and Challenges

Throughout nearly 14 years of debilitating conflict, Syria became a geopolitical battleground, in which Russia, Iran, Turkey, the United States, Israel, and dozens of other governments engaged directly and through local partners in pursuing a wide range of security interests and priorities. While Bashar al-Assad and his regime stalwartly refused to submit to meaningful negotiations over the years, the security implications of a seemingly intractable conflict continued to grow. From a globally consequential displacement crisis to a multibillion-dollar transnational drug smuggling network, international terrorism, proliferation of strategic weapons, and more, Syria has presented the international community with a formidable array of security threats.

It was the severity and persistence of these security challenges that led a steadily growing list of countries to begin re-engaging Assad’s regime in recent years. Fatigued by confronting the many spillover effects of Syria’s crisis, exasperated by the lack of diplomatic progress on resolving it, and resigned to Assad’s survival or even victory, a number of Arab and Middle Eastern governments and even some European leaders began a policy of de facto normalization in 2022. For regional states, engaging Assad and re-admitting him to the Arab League21 was intended as an attempt to coax him into helping to resolve the drivers and causes of their priority concerns: refugees, drugs, and terrorism. For those in Europe who were re-engaging Assad’s regime, anti-refugee sentiment was the impetus and justification.22

Yet for all who tried engagement and normalization, Assad proved to be no ally or partner. Amid the peak of regional engagement with Assad’s regime — from mid-2023 into early 2024 — the threats and challenges posed by refugees, drugs, and terrorism did not improve; they deteriorated.23 As normalization’s failure became increasingly clear, a sense of diplomatic stagnation returned.

Buoyed by the West’s gradual disengagement from Syria and the decision by others to re-engage, Assad grew convinced of his own inevitable victory. Syria’s military and security apparatus, already exhausted and riddled with warlordism and corruption, devolved into a state of increasing stagnation.24 The precipitous collapse of Syria’s economy in 2019-20 and a resulting liquidity crisis created conditions in which traditional lines of loyalty between the regime elite and Assad were gradually eroded by a surge in organized criminal activity.

While governments and other external stakeholders had accepted Assad’s inevitable victory, Syria’s armed opposition had not. Throughout the four-year period of “frozen conflict,” armed groups in northwestern Syria, led by HTS, were methodically and determinedly preparing to challenge the regime’s rule once again. Through the establishment of formal military academies and intensive training, and the addition of new capabilities such as night-time combat, drone warfare, and more effective rocket and missile systems, an HTS-led alliance grew in capacity — while its regime opponents decayed.25

Therefore, when HTS launched a concerted offensive into Aleppo’s western countryside on Nov. 27, 2024, the conditions had already been set for a significant shift in the power balance on the battlefield. Aleppo City fell within 36 hours; and 10 days later, the Assad regime had collapsed like a house of cards. Assad fled to Moscow and Damascus fell to opposition and HTS control on Dec. 8. The assessments and assumptions that had undergirded an evolving international policy on Syria were, in very short order, turned swiftly on their head.

Assad’s Departure Brings Security Benefits

The fall of Assad’s regime in December 2024 brought sudden and dramatic improvements to some of the longest-standing security challenges involving the country. On the one hand, Iran was dealt a crippling defeat, with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) leaving Syria altogether, along with thousands of its proxy militiamen from Lebanon, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Iran’s military bases in Deir ez-Zour, rocket launch sites in southern and eastern Syria, economic investments, and religious and cultural facilities were all swiftly vacated. With no partners left in the country, it remains hard to envision Iran finding a way back into Syria.

Having committed years of war crimes in Syria and utilized its Khmeimim Airbase and Tartous naval base as launching pads for expansive operations in the African continent, Russia also suffered a significant defeat with Assad’s loss. While Moscow did grant Assad and his family asylum, it also pivoted pragmatically toward the new HTS-led interim government — first seeking to secure the safety of Russian troops deployed in posts across Syria and then to negotiate the future status of its bases on the Mediterranean coast. Despite its flexibility toward Syria’s new authorities — including diplomatic contact, cash deliveries, and talks over retaining its bases — there can be no doubting Russia’s strategic losses in Syria since December 2024.

The rapid collapse of Assad’s regime also dealt a killer blow to the multibillion-dollar industrial drug trade that prominent elements of the regime had fostered in previous years. Having been coordinated primarily by the regime’s elite Fourth Division, the production and smuggling of captagon across Syria’s borders has all but vanished since. The interim government and its Ministry of Interior’s General Security Service (GSS) have taken the lead in locating and destroying large-scale production facilities as well as rooting out smuggler networks and dealers in dozens of raids across Syria between January and March 2025.

For over a decade, the strain of hosting millions of Syrian refugees had crippled the economies of several regional states, but the end of Assad’s regime removed the primary obstacle deterring those Syrians from returning home. While UN polling in April 2024 indicated that just 1.7% of Syrian refugees would consider an eventual return under the prevailing conditions at the time, by January 2025 that number had spiked to 27%.26 Between Assad’s fall on Dec. 8, 2024, and mid-February 2025, at least 280,000 refugees came back to Syria from abroad, and a further 800,000 internally displaced Syrians returned to their homes.27 Many refugees may choose to wait some time to ensure that a post-Assad Syria remains stable. But the early signs on return are extremely encouraging not only for Syria but also for the refugee host states. Of course, the security situation on the ground, including the presence or absence of extra-legal militias and terrorist groups, will be one of the key determining factors behind the rapidity and size of the initial wave of returnees.

The HTS Dilemma

As the dominant component of Syria’s ongoing transition, HTS itself presents the international community with a not insignificant dilemma. After all, HTS began life in 2011 as the Syrian wing of the Islamic State in Iraq, before turning against ISIS in 2013 and declaring itself al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, only to break ties with al-Qaeda and declare independence in 2016. However, since becoming HTS in mid-2016, the group has changed considerably — disavowing global jihad in favor of Syria’s revolution. Over the past eight years, HTS arguably underwent an unprecedented evolution within the Salafi-jihadi world, turning its guns on ISIS and al-Qaeda in northwestern Syria,28 dealing strategic defeats to both movements.

Beginning in 2017, HTS facilitated the presence of Turkish troops within its territory; and from 2020, it agreed to and abided by a cease-fire brokered by Turkey and Russia. HTS also established a technocratic “Salvation Government” in Idlib that, in most respects, delivered a greater and more efficient level of services than rival regions of Syria. The group has spent years reaching out to and building lines of communication (mostly behind closed doors) with the international community, including government actors in Europe and the United States. It has also purged itself of hardline elements unwilling to accept its more pragmatic path in recent years and forcefully expelled a number of independent foreign fighter factions for the same reason. Finally, it is widely understood that HTS has provided actionable intelligence on ISIS and al-Qaeda operatives for use by foreign intelligence agencies.

While the lead role currently being played by HTS in Syria’s transition is unquestionably far from ideal,29 Ahmed al-Sharaa and his interim government have, by and large, behaved pragmatically and responsibly. The sustained and high-level diplomatic engagement by Europe, regional states, the UN, multilateral institutions, and other significant political bodies points to an acknowledgement of Syria now offering a more open and constructive posture than anything offered previously by Assad’s regime. Given the enormity of the transitional challenges ahead, this engagement is a good thing. Further engagement provides a far greater chance to incentivize more good behavior and a broadening of the transition to better reflect Syria’s diversity than a policy of isolation.

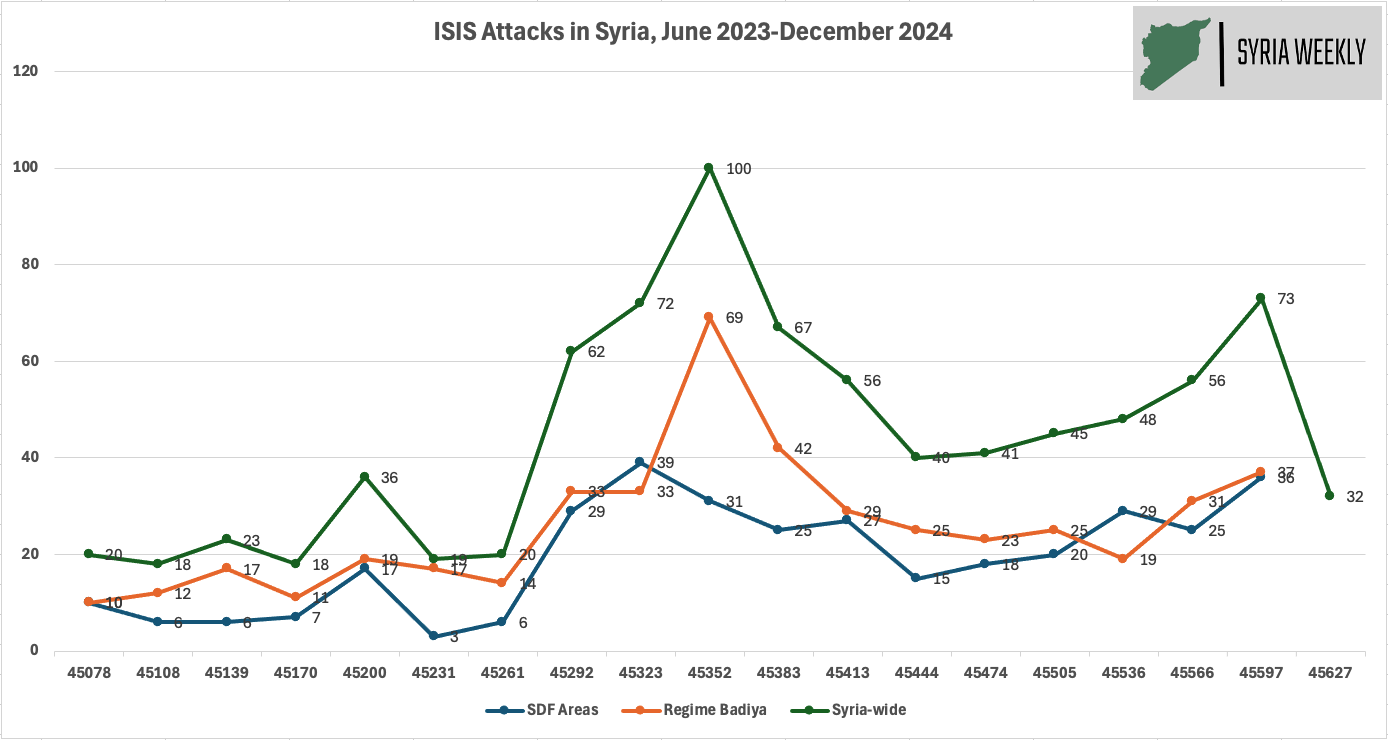

The ISIS Challenge

Perhaps the most consistent subject of international security attention in Syria over the years has been the threat posed by ISIS. While the terror group was dealt a territorial defeat in early 2019 in the eastern village of al-Baghouz in Deir ez-Zour, it has slowly recovered in the years since. By 2024, ISIS was resurgent in Syria — tripling the number of attacks it carried out compared to 2023 and more than doubling the average number of people killed per attack, while expanding its geographic reach, operational sophistication, and recruitment.30 All in all, red alarm bells were flashing as 2024 drew to a close.

However, the most significant and consistent driver of ISIS activity in Syria had been Assad’s regime, the brutality and corruption of which fueled the instability, chaos, suffering, fear, and uncertainty that drove ISIS recruitment and which the group used to justify its actions on the ground. With Assad gone, ISIS’s presence in Syria almost vanished, as operatives redeployed next door to Iraq or went to ground in Deir ez-Zour’s eastern desert. For the first time, the US-led coalition operating out of Iraq and northeastern Syria now has unfettered access to monitor and strike ISIS targets anywhere in the country. In the days following Assad’s fall, dozens of US strikes hit ISIS operatives in formerly regime-held areas.31

While Syria’s interim government lacks the manpower and resources to comprehensively deal with ISIS, its Sunni Arab-dominated armed forces represent a far more natural antidote to the jihadi group than any other armed actor operating in Syria. As the de facto ruling authority in northwestern Syria since 2017, HTS and security forces associated with its Salvation Government coordinated a years-long campaign against ISIS that practically eradicated the group from the region altogether.32 Since taking the reins in Damascus, the HTS-dominated GSS has foiled at least eight ISIS terror plots, most directed at key urban centers like Damascus.33 The interim government’s recent counterterrorism success against ISIS is, in large part, thanks to a fledgling security relationship with the US — at both the intelligence and military levels.34

The first direct and acknowledged contact between the US military and Syria’s interim government took place on Dec. 13, 2024, when a US citizen (Travis Timmerman) found in a regime detention center was handed over to US soldiers on Syrian soil.35 One week later, on Dec. 20, 2024, Maj. Gen. Kevin Leahy (commander of Combined Joint Task Force Operation Inherent Resolve, CJTF-OIR) joined a senior State Department delegation in Damascus for meetings with Syria’s interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa and Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaybani.36 Since then, US Central Command (CENTCOM) and Special Operations Command (SOCOM) have remained in direct contact with Damascus on a near-daily basis — to deconflict troop movements, to coordinate on occasional counter-ISIS operations, and to generally establish a reliable line of communication.

Meanwhile, the US intelligence community has also established a fruitful relationship with Syria’s interim government, coordinated through the Ministry of Interior and its minister, Anas Khattab. In addition to the eight foiled ISIS plots, it is believed that a spate of recent US drone strikes targeting al-Qaeda operatives in northwestern Syria were also linked to the fledgling intelligence-sharing relationship between Damascus and Washington.

However, the ISIS threat persists; and while the prevailing dynamic has avoided any significant ISIS escalation, fledgling counterterrorism cooperation between the US-led coalition and the interim government in Damascus is extremely fragile and heavily reliant on a continued US military presence on Syrian soil. Worryingly, ISIS attacks markedly intensified in the first week of March 2025,37 and it is widely feared that ISIS maintains a significant network of sleeper cells in Syrian cities.

An Assad Loyalist Resistance?

A significant dynamic that accelerated the collapse of the Assad regime over 11 days in late 2024 was the failure — or refusal — of military forces to hold the line on the battlefield. Instead, a series of game-changing surrenders or peaceful handovers took place through Hama and into Homs, clearing a path to Damascus. As the frontline moved forward, Syrian soldiers removed their uniforms, abandoned their weapons, and simply went home.

After assuming control in Damascus, the HTS-led interim government announced the complete dissolution of the Syrian Arab Army and called for former military and security personnel to voluntarily register and “settle” their status.38 In doing so, tens of thousands of men have gone through varying levels of security investigation, to be cleared for reenlistment or a return to civilian life.

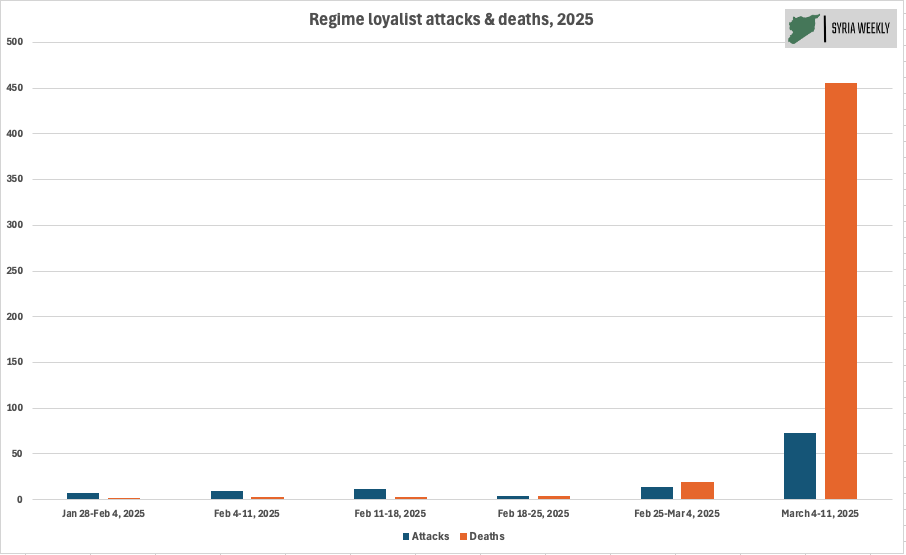

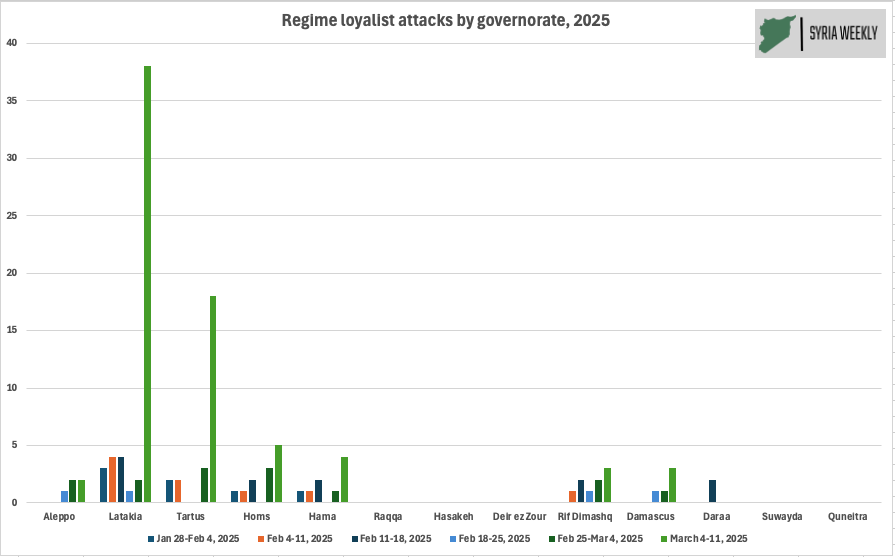

While that process has played out, some former regime soldiers and intelligence officers have clearly chosen to go into hiding. An interview in Damascus in early-February 2025 revealed that 4,000-5,000 men in Latakia and Tartous were known to have evaded the settlement process. Across the country, some were caught in a nationwide campaign of daily search operations and targeted raids, but others have taken to a campaign of armed resistance against the interim government. In February 2025, at least 38 insurgent-type attacks targeted the interim government’s GSS, Public Security, and Department of Military Operations (DMO) forces in Latakia, Tartous, Homs, Hama, Aleppo, and Rif Dimashq governorates.39 Though this activity remained relatively minor in scale — resulting in just 30 deaths — it was indicative of an emerging new danger.

That danger revealed itself late on March 6, when regime loyalists launched an unprecedentedly large campaign of coordinated ambushes, raids, and other attacks on interim government forces in Latakia and parts of Tartous. What followed in the hours and days after was a frenzy of violence, as Alawite pro-regime gunmen turned on rival villages and vice-versa; and interim government forces, foreign jihadist fighters, and armed Syrian men all engaged in retaliatory and revenge attacks. After 48 hours, hundreds of combatants and hundreds of civilians were dead on all sides and Syrians’ worst fears — of a return to brutal conflict, in which sectarianism was the defining feature — appeared to have been realized. The intensity of conflict declined markedly from March 9, but tensions have remained high. Efforts by the interim government in Damascus to investigate crimes and pursue perpetrators were an encouraging first step, but the violence served to underline that keeping a lid on a boiling pot of civil tensions after more than a decade of ferocious conflict will prove an extraordinary challenge going forward.

The Forgotten

In addition to HTS and a wide spectrum of Syrian armed opposition factions, the dramatic offensive that entered Damascus on Dec. 8, 2024, also involved several smaller jihadist groups headquartered in Idlib. From the Uyghur-dominated Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) and the Central Asian Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad (KTWJ) to a number of other smaller foreign fighter units dedicated primarily to providing specialist training courses, these jihadis now face an uncertain future in the new, post-Assad Syria.

Sharaa had initially proposed naturalizing many of these fighters as a reward for their role in the armed struggle,40 but pressure from the international community appears to have put a stop to that. In the meantime, the interim government’s approach seems to be oriented toward rewarding local foreign fighter leaders — likely in an attempt to sustain a semblance of loyalty and obedience from their fighters. Most notably, several prominent foreign jihadi commanders have been promoted to positions of command within Syria’s new Ministry of Defense. This includes Brig. Gen. Mohammed Jaftashi (Mukhtar al-Turki), the new commander of Damascus command; Brig. Gen. Abdulrahman al-Khatib (Abu Hussein al-Urduni), the commander of the Republican Guard; TIP leader Abdulaziz Dawoud Khudaberdi (Zahid) and commander of the Albanian Xhemati Alban faction, Abdul Jashari (Abu Qatada al-Albani), who were made brigadier generals; and TIP commanders Mawlan Tarsun Abdussamad and Abdulsalam Yasin Ahmed, who were made colonels.

As the most sizable foreign fighter faction, the TIP has received the most institutional recompense. For years, the northwestern Idlib city of Jisr al-Shughour has been the TIP’s de facto capital, with the group’s approximately 2,000 fighters joined by thousands more family members — women, children, and the elderly. In addition to retaining a favored status in the region and continued business investments within the new post-Assad Syrian economy, the TIP was recently publicly rewarded with free education through university for all related children.41

While such financial and institutional inducements are likely to maintain a stable balance for now, there is a substantial risk that the presence of thousands of jihadist fighters in northwest Syria will eventually become unstable. Until December 2024, living conditions in that area were markedly superior to anywhere else in the country; but with time, it seems inevitable that the central government’s will and ability to invest in Syria’s outer regions as much as in the major urban centers will decline. The appointment of Alaa Omar al-Ali (who previously headed up the Chamber of Trade and Industry in HTS-run Idlib) as the new president of Syria’s Chambers of Commerce could be a sign that the interim government is aware of this danger.42 Nevertheless, should Syria’s outer regions once again be deprioritized, as was long the case before the war, at least some of these men — and their next generation — will become ripe opportunities for recruitment, particularly by al-Qaeda but potentially also ISIS.

The Structural Challenge: Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration

The most significant and strategic challenge for Syria’s transition is the need to accomplish the DDR of tens of thousands of armed fighters, soldiers, and conscripts across the country. After nearly 14 years of intensive, nationwide conflict, this challenge is enormous.

Substantial progress has been made in transitioning HTS and its various Syrian faction partners into the backbone of a new military force, and a deal has been signed under which the SDF will be integrated into the Syrian state. Meanwhile, negotiations continue with armed groups in the southern governorates of Daraa and Suwayda. Daraa’s several thousand fighters, collectively under the command of Ahmed al-Awdah and his deputies — Col. Nassim Abu Ara (Abu Hossam), Lt. Col. Mohammed al-Hawrani (Abu Issam), and Capt. Mohammed al-Qadri (Abu Haydar) — remain the subject of negotiations with Minister of Defense Murhaf Abu Qasra. Suwayda’s most influential armed factions — Liwa al-Jabal, Ahrar al-Jabal, and Rijal al-Karama — have engaged in regular dialogue in Damascus with Sharaa, but their demands for greater autonomy, as well as for a more distinct, decentralized form of governance for Suwayda, make for a more complex process.

The thorniest issue has been achieving a deal between Damascus and the SDF in northeastern Syria. Since the fall of Assad’s regime, a palpable Syrian consensus has emerged that prioritizes unity and views demands for semi-autonomy and decentralization with acute suspicion. That has weakened the SDF’s negotiating position significantly and presents a potentially existential threat to its political front, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), and governance arm, the AANES. With US military encouragement and facilitation, the SDF and Damascus engaged in direct, high-level negotiations, and agreed on the core architecture of a deal on March 10, 2025, involving the SDF’s dissolution and integration into the state. But the devil is in the details, and the implementation of the deal will take time.43